Coral Reefs and Ocean Acidification

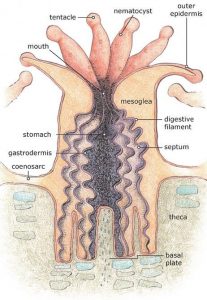

Coral reefs are some of the most important habitats that have developed over hundreds of millions of years on Earth. Most people believe that corals are plants, but they are actually invertebrates with simple stomachs and a single mouth, much like jelly fish and sea anemone. Although they roughly occupy less than 1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs are home to about 25% of all ocean species! They comprise the largest living structure in the world and can even be seen from outer space, and with all that biodiversity they are important to much more than just themselves. Unfortunately, coral reefs are diminishing right before our eyes with climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and ocean acidification altering our oceans water chemistry.

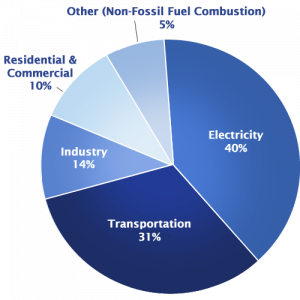

Ocean acidification has caused the chemistry of our oceans to change drastically in a relatively short period of time. Since the industrial revolution, the burning of fossil fuels for cars, industries and electricity has left the world in a cloud of continual CO2 emissions that collect in the atmosphere. With our oceans taking up about two-thirds of Earth’s surface, they are the largest source of CO2 removal from air. The oceans remove about one-third of all CO2 emissions from the atmosphere, but when too much carbon dioxide is absorbed into our oceans it can be harmful to the animals living within them.

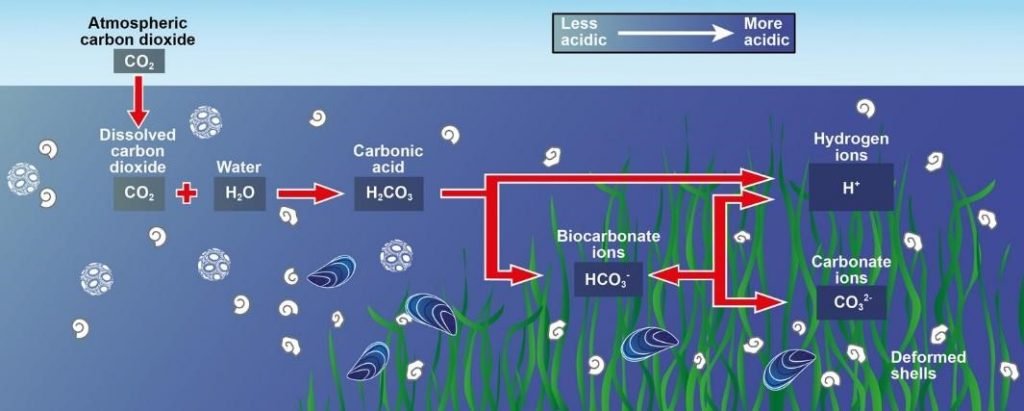

When CO2 is introduced to saltwater, it causes complex chemical reactions that ultimately increase the acidity of the water. Ocean water pH stayed stable over the last 300 million years, around 8.2, which is the most comfortable region for corals to grow and flourish. Since the industrial revolution, we have seen a pH shift from 8.2 to around 8.1 and 8.0 in certain regions of the world. Although a 0.1 or 0.2 decrease in pH seems extremely small, it actually accounts for a 25% increase in acidity in only 100 years! These drastic changes in the pH and temperature of the oceans in a very short period has left many of our animals in shock, especially our corals.

Corals natural environment and comfortable living conditions are quickly changing in a way that’s not unlike animals that lose their habitats to deforestation or natural disasters. Most corals are not able to acclimate to the more acidic environments that have come about in the last 100 years. In turn, corals become so stressed out by the changing water chemistry that they ultimately undergo coral bleaching events.

Individual corals are called polyps and multiple coral polyps in an area are called a colony. There are both hard and soft corals that live in the ocean, but most of us have seen hard corals that live in shallow tropical waters. These hard corals have a calcium carbonate structure that would be similar to our bones. Polyps grow off this skeleton that contain algae called zooxanthellae. Zooxanthellae not only give corals their bright, vibrant colors, but also support the life of these corals by helping trap food and offering protection.

During coral bleaching, acidic waters cause corals to “kick out” the zooxanthellae living in their polyps. Once this happens, the coral is not able to protect itself or get the food it needs and in turn, the polyps begin to peel off the skeleton like fleshy material until only the calcium carbonate skeleton is left.

So why should we care about coral bleaching? First of all, corals are one of best places for life to flourish! With nearly 25% of all ocean species living on or near coral reefs, they offer homes, protection and food for many animals. Coral reefs are also a great barrier to coastal areas when there are hurricanes and rough waters as they block water from flooding and destroying natural coastal regions. Additionally, tourism in many places will drop off without the reefs. Some regions depend on the natural beauty of coral reefs as a source of income for aquatic excursions.

Even though it might sound like corals as we know them have come to their end, there are steps we can take to have a positive impact. Educating ourselves and others about the harmful effects of CO2 emissions is a critical step. Emphasizing careful viewing of corals is also important. (Humans shouldn’t touch, pick up or take home wild corals any more than we should sharks, eels, jellyfish and other living things.) We can support research institutions such as Mote Marine Laboratory or the Coral Restoration Foundation Education Center that are devoted to learning more about coral and saving our reefs. And, most directly, we can cut down on our CO2 emissions in any way possible. This could mean using less energy and water at home, riding bikes to school or carpooling to the places you need to go, recycling products we use every day and making sure we aren’t polluting our water ways. For more information about coral bleaching, check out Chasing Corals, an amazing Netflix documentary that shows the harmful effects of coral bleaching and highlights some of the great people out there working to restore our reefs. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6fHA9R2cKI